By Dennis LimThe New York Times. July 9, 2006

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia:

"YOU haven't seen the movie," the director Amir Muhammad said, addressing the small crowd that had come to hear him talk about the most controversial Malaysian film of the year. "Now buy the T-shirt."

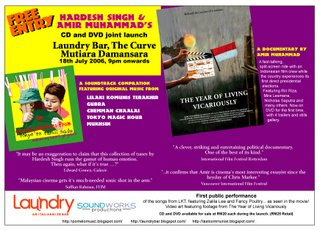

Mr. Amir, 34, is one of this country's leading independent filmmakers, and from the point of view of the authorities, something of a pest. His newest film,

The Last Communist, is, as he puts it, "a semi-musical documentary road movie" based on the life of Chin Peng, once the leader of the outlawed Malayan Communist Party. (Mr. Chin, now 84, is an exile in Thailand.) It was to have been the first local documentary to open theatrically in Malaysia. Instead, it is the first Malaysian film to be banned at home.

Forbidden to screen the film even in private settings, Mr. Amir has been speaking out about the ban. On a recent Sunday, at an event sponsored by a political publisher, he previewed the film's trailer, relayed news of its DVD release in Singapore (cautioning that possession of the film in Malaysia constitutes a criminal offense) and sold

The Last Communist T-shirts to recoup some of the lost box-office revenue.

After the movie had its premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in February, Mr. Amir submitted it to the Malaysian censorship board, which passed it for release without cuts. Because of its eyebrow-raising title — Communism is a taboo topic here, a legacy of the Malayan emergency of the 1940's and 50's, when the British colonials battled a ragtag but dogged Communist insurrection — he was asked to screen the film for the Special Branch, the arm of the police force responsible for internal security. Mr. Amir said the officers who attended had no complaints, though, he added, "one of them said people might be bored."

In May, two weeks before the film was set to open, Berita Harian, a conservative local daily, published a series of articles denouncing the film as a glorification of Communism. None of the journalists involved, or the historians and politicians they quoted in the articles, had seen the film or asked to see it, Mr. Amir said.

On May 5 the Home Affairs Ministry, which oversees the censorship board, retracted its approval, citing public protest. The ban set off a flood of media commentary, much of it questioning the ministry's decision. After a screening was held for Malaysian members of Parliament, the home minister, Radzi Sheikh Ahmad, said the real problem was that the absence of violence in the documentary could create the misconception that Chin Peng was not himself violent. "It will be like allowing a film portraying Osama bin Laden as a humble and charitable man to be screened in the United States," Mr. Radzi told a local newspaper.

Mr. Amir said, "I think this is the first time a film has been banned for not being violent enough."

Earlier bans have earned the censorship board here a reputation for being both draconian and capricious.

Schindler's List was deemed Zionist propaganda.

Zoolander, in which Will Ferrell's character tries to assassinate the Malaysian prime minister, was thought unsuitable for obvious reasons.

Daredevil was blacklisted because its superhero sounded, well, satanic.

Malaysian censors have long taken their cue from the autocratic style of Mahathir Mohamad, the former prime minister who stepped down in 2003 after 22 years in power. The attitudes of the cultural gatekeepers provide a window into the contradictions and tensions unique to this multiracial, polyglot society, which has a politically dominant Malay Muslim majority and sizable minorities of ethnic Chinese and Indians.

Within Kuala Lumpur's small group of independent filmmakers, Mr. Amir is a distinctive voice. A law school graduate and occasional newspaper columnist, he has concentrated on reviving the lost art of the film essay for a society that hasn't always had much to balance the official narrative.

"There are 15 universities in Malaysia, and only one has a history department," Mr. Amir said. Accordingly, his films function as sardonic memory aids.

The Big Durian (2003), named for a thorny local fruit, is a meditation on Malaysian racial politics, revisiting the 1969 riots between Malays and Chinese, and the government's 1987 Internal Security Act clampdown, in which more than 100 activists and artists were detained and several newspapers shut down.

Combining real and scripted interviews,

The Big Durian vividly shows how national traumas can, in a culture of opacity and evasiveness, be collectively forgotten. The film, the first Malaysian movie shown at the Sundance Film Festival, was never submitted for the censors' approval — its head-on approach to the prickly subject of race would seem destined to disqualify it immediately — and has only screened at movie clubs here.

Mr. Amir made

The Last Communist because he was intrigued by the demonization of Communism in history textbooks and government statements. Commonly termed traitors, the Communists were widely viewed as rabid nationalists who, after fighting alongside the British against the Japanese occupiers in World War II, mounted a guerrilla insurgency against the colonial rulers.

Using Chin Peng's 2003 memoir,

My Side of History, as a road map,

The Last Communist passes through the small towns where Mr. Chin, the son of Chinese immigrants, lived from his days as a student Communist leader to his time on the run as the most wanted man in the British empire. In these sleepy backwaters Mr. Amir interviewed dozens of locals, mainly about their day-to-day work lives.

The resulting travelogue, punctuated by musical numbers spoofing the songs from the instructional films the British used to circulate, poses sidelong questions about empire, patriotism and national identity. Details from Mr. Chin's life appear as on-screen text, but the man himself is conspicuously absent. Not a single photograph is shown; the only likeness is a cartoon.

"I didn't want to use archival stuff," said Mr. Amir. "That's such a comfortable way of presenting history. The idea was to show that history happens in the present tense."

Mr. Amir, who is Malay Muslim, believes the controversy surrounding his film, like so much else in this country, may be less a matter of ideology than race. The ban appears to have resulted from the pressure applied by

Berita Harian, a paper whose politics Mr. Amir classified in a recent blog entry as "verging on the ethnocentric and semifascist." One of its editorials advised Mr. Amir to stick to documenting the lives of Malay heroes. (Most Malaysian Communists were of Chinese descent.)

Though disappointed about the ban, Mr. Amir is busy with other projects. He is finishing a horror movie,

Susuk, and is about to start a publishing house. He plans to write the first title himself: a volume of political humor called

Malaysian Politicians Say the Darndest Things.

He's also shooting a sequel to

The Last Communist. The first film took him to Betong, a village in southern Thailand where Malaysian Chinese Communists live in exile. This time he's heading to another Thai village, Sukhrin, where the few Malay Communists settled. Given the switch in racial emphasis, Mr. Amir expects the official response to be telling. "If they're smart, the government would ban this one too," he said. "Otherwise it might expose their hypocrisy."